Classism & Photography

A short essay of poverty, "isms" and questions about the images we consume.

We just wrapped up a family photo shoot this weekend and it got me thinking: if photographs were to tell a story of our generational wealth, what would they say?

Professor Brittney Cooper aka Professor Crunk’s explanation of “ism” in her book Eloquent Rage: A Black Feminist Discovers Her Super Power hit to the core of my bones, giving me chills and resonating in a way I’d never thought about “isms” before.

“Sexism, like every other “ism,” is a willful refusal to not see what is right in front of you.”

Last year, I had the opportunity to speak with a woman from a non-profit housing coalition here in Sacramento. Her organization advocates at the capital on behalf of the city of Sacramento because our city, like many, is experiencing a housing crisis. Lower-income to middle-income families are being evicted left and right from their homes and they can’t afford the city’s rents. As wealthier people move from the Bay Area to Sacramento with the advantage of being able to work remotely, the city and its policies are ill-equipped to handle the transition. Living in midtown the last couple of years I’ve watched this truth unfold right in front of my eyes.

Our unhoused population increased by 67% going from 5,000 to almost 10,000 since 2019.

When Riley was born we had the privilege of both being able to take maternity and paternity leave. We’d go on long walks through midtown to the co-op and back. We’d fill our fancy stroller up with groceries for the week. But our “social mobility” wasn’t lost on us. My sister pointed that phrase out recently on Facebook, as she celebrated getting braces.

“According to the Centers for Disease Control, 17% of low-income children between the ages of two and five have untreated cavities in the U.S., and this number jumps to 23% when they become adolescents. In addition to the long-term health effects of not being proactive about dental care, having "bad teeth" can be shameful for kids and teenagers and can be a barrier to employment as an adult.” from my Newsweek Expert Forum article, How Gaps in Pediatric Dental Care Fuel Cycles of Poverty and What We Can Do About It

When Riley was 5 weeks old we were on one of our daily walks when we ran into a family with a mini-van, full of things, and a little boy maybe two years old playing on the sidewalk. The father was talking to his friend about how they had to move. It sounded like it was unexpected. It sounded familiar. I remember hearing stories from my biological mother about how the church vouchers for motels only lasted a couple of weeks. The little boy’s dad asked us where the nearest motels were. I wondered if that little boy would have photographs of his childhood by the time he is my age.

As I write this piece, I’m staring at an old photo album being held together by its mere binding. It’s one of four or five photo albums of my childhood. Much of my biological family’s history has been lost to re-possed storage units. My younger siblings were four and seven years old when our family fell apart. They have even fewer photos of themselves.

When people are living out of their cars generational keepsakes are easily misplaced.

It’s one thing to read in the paper from the comfort of your suburban neighborhood that the unhoused population is growing. It’s another to wake up to a young girl walking past your house wrapped in a large fleece blanket using it as a coat. She was maybe 15 years old. And I thought about the time I was roofied in college.

“My next memory is of being shoved into a bathroom by a nurse, my toes curling at the cold linoleum floor, shivering under the paper-thin hospital gown. She shouted at me to get dressed, throwing a bag of vomit-covered, tattered clothing in my direction. In a daze, I grabbed onto the long metal handicap bar to orient myself. I didn’t know where I was. I walked through the emergency room and eventually, someone pointed me in the direction of the dorms. I hiked a half mile in my high-heeled, strappy knee-high boots, trying my best to hold together the back of the hospital gown.

A security guard in a van started following me. I was terrified, shaken, numb, and walking as fast as my slut boots would allow. In retrospect, he was probably just making sure I made it to campus safely. I got to my dorm, showered the vomit from my hair, and sank to the floor crying under the warm water. As the tears and water rolled down my face, I examined foreign limbs that were supposed to be my own and a shell of bruises that covered my shattered and cracked body. It looked like I’d been hit by a car. My knees were cut and bloodied, and a porous ocean of purple and blue ran up my thigh to my hip. What happened?”

That night I had set my drink down to take a photo. All too often we expect victims to pull themselves up by their bootstraps, with little to no resources but poverty is complex, traumatic, and can’t be solved by a convenient one size fits all treatment plan.

I don’t think there is a day that goes by when someone doesn’t take a photo of our son. We already have hundreds of videos and pictures. He’s barely a year old.

Ephemera is one of those things that the art historian in me wants to hold onto forever. I can’t help but think about all the histories that are lost to oppression. How else will we breed compassion if we silence difference?

Sure, some might say, “But Melissa look at all you’ve done.” And it’s easy to fall prey to the individualistic narratives of the American dream. I was a high school dropout when a small-town community band together to help me graduate and pursue an education which landed me in rooms where social mobility became possible. I had access to both mental and medical healthcare at a young age.

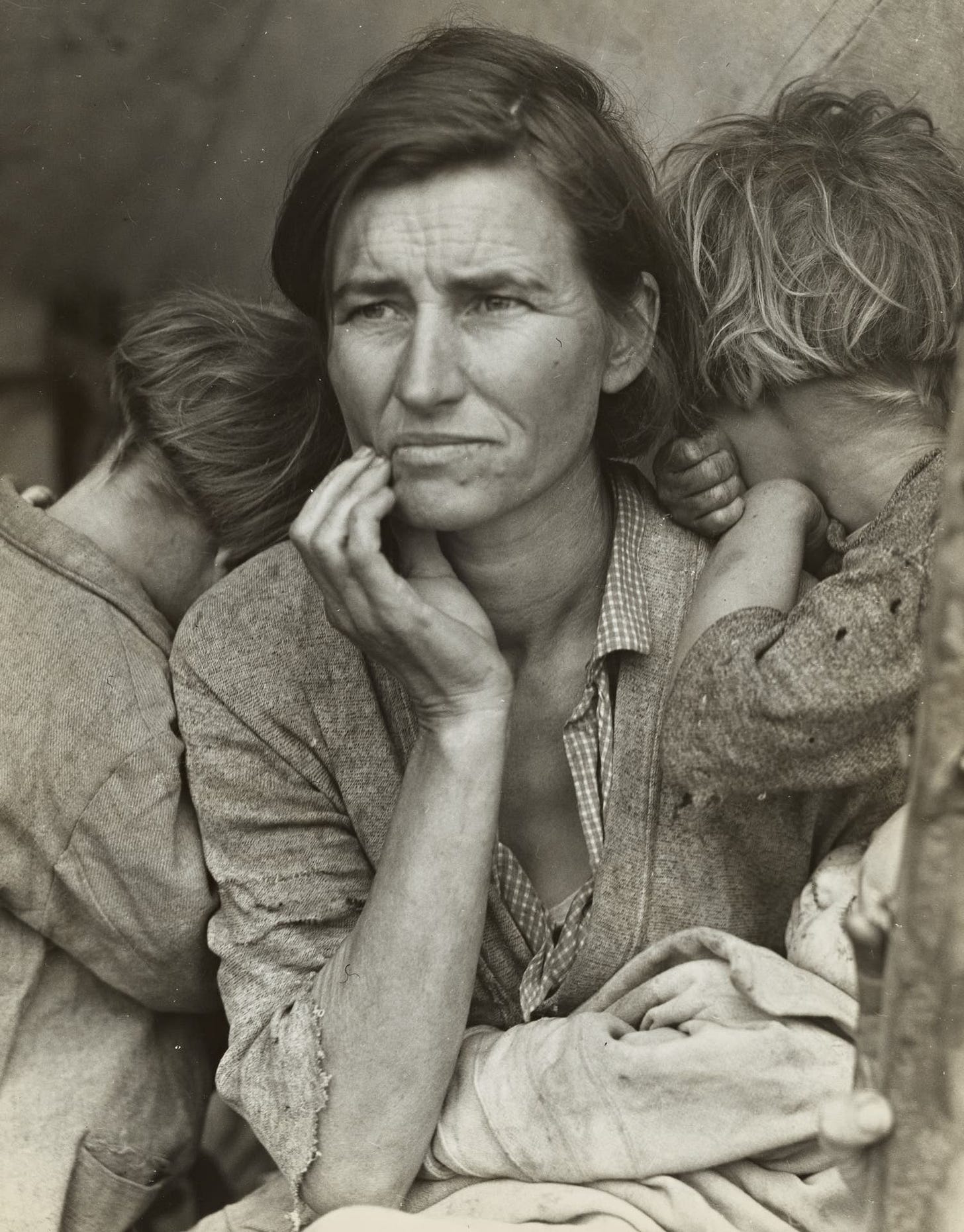

I think of the famous image of Florence Owens Thompson in Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother. I wasn’t surprised to hear she was indigenous and felt exploited by the image. ( ***I’d like to note here that it didn’t come naturally to me to put Florence's name in front of Dorothea’s. Her name isn’t even mentioned in the bi-line for the piece that talks about her own exploitation. The “isms” are so deeply embedded in us that our first instinct is often to praise the artist, not the subject.)

“Thompson and her children disputed other details in Lange’s account and sought to dispel the image of themselves as stereotypical Dust Bowl refugees.

Born in Oklahoma, Thompson was actually a full-blooded Native American; both her parents were Cherokee. In the mid-1920s, she and her first husband, Cleo Owens, moved to California, where they found mill and farm work. Cleo died of tuberculosis in 1931, and Florence was left to support six children by picking cotton and other crops.”

As the gap between the classes increases, we have to start asking ourselves what is our role in these systems. And what “isms” are we missing in the content we digest every day?

In therapy we learn, naming it is the first step.